The Belcanto Tradition - Not just for Singers - And how Music relies on It

Intro

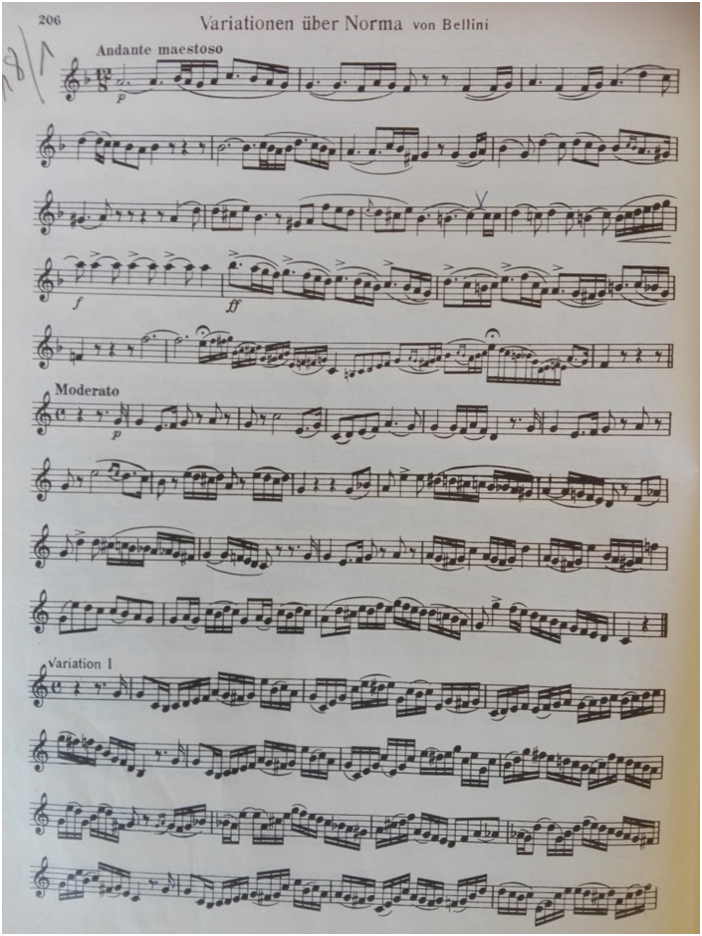

While browsing through the scores my father, the former solo trombone at the Südwestfunk Symphony Orchestra and master class student of the chamber virtuoso Konrad Bruns, left me, I was surprised by the number of pieces that clearly belong to the belcanto tradition. I discovered fatansias, capriccios and solo pieces that clearly emphasized the romantic ideal of the 19th century: beautiful sound. “Beautiful singing” (that’s what “belcanto” means in Italian) used to be the ultimate aim of European vocalists. By this I mean the beauty and virtuoso shaping of musical phrases as well as the senses. The heart of this tradition was to be found — you guessed it — in Italy. Composers like Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini wrote operatic arias that caused the belcanto tradition to peak. Audiences in those days used to consider the performers of such arias heroes, or even musical gods. It isn’t difficult to imagine a frenetic audience shouting “bravo, bravissimo” at the end of a beautifully delivered belcanto aria. Belcanto was considered the direct path to the human soul.

Belcanto for Instrumentalists

Obviously, instrumentalists were just as eager to reach this sonic ideal. This triggered the emergence of the so-called “virtuoso style”: famous operatic arias were arranged by well-known soloists who adapted them to their instrument. This was deemed necessary, because the solo literature available at the time no longer met the expectations of “solo virtuosos”. In addition, the invention of valves added a chromatic dimension to the instrument. Jean Baptiste Arban duly expanded his trumpet method with belcanto arias by the most famous Italian composers. The “Variations on a Theme” genre proved a major boost for instrumental scores and quickly became a genre in its own right (O du lieber Augustin/Carnival of Venice, etc.).

New Music as a Counter-Reaction

Konrad Bruns, the former solo trombone at Semperoper in Dresden and my father’s teacher, had grown up in this tradition of beautiful melody crafting. In his classes, he focused on romantic pieces and how to play them, while he also composed his own belcanto-inspired cadenza for the David Concerto (see the Nagold brass scores published by Schmid).

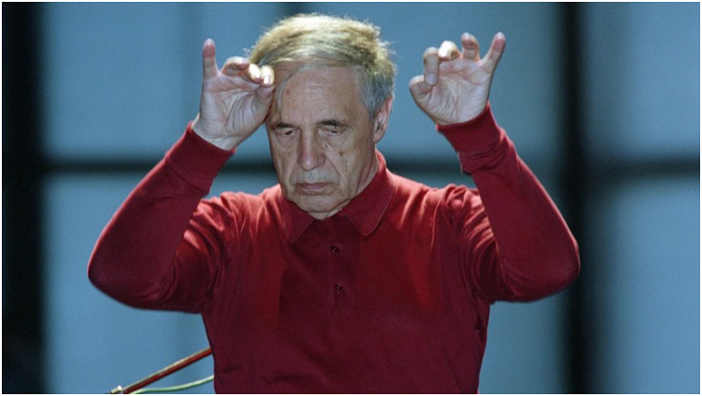

After leaving the Karlsruhe Theater for Südwestfunk in Baden-Baden, my father had to radically change his solo trombone style and to come to grips with a completely different genre. After World War II, Heinrich Strobel, the first head of the music department at Südwestfunk, together with the French occupying power, changed the course of this broadcasting station with the intention to create a modern, open and future-oriented institution, with ample room for contemporary composers. In 1968, he set up the “SWR Experimental Studio” for electronic and live electronic music. The “Donaueschingen Festival” quickly lured contemporary composers like Igor Strawinsky und Paul Hindemith to Baden-Baden, who were later followed by avant-garde composers like Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Luigi Nono. Electronic music as a symbol of industrialization and mechanization became the model for instrumental music. Pierre Boulez’ minimalist conducting style leaves no doubt about what was expected from orchestral musicians in those days — faithful interpretations and clarity. I still vividly remember that time when Boulez stayed at my parents’ place, by the way.

New Sobriety

This current put the belcanto tradition to rest. Clarity, sobriety and precision were suddenly more important than a beautiful tone. Embellishments, ornaments, vibrato or romantic melody shaping were frowned-upon and considered old-school. This new sobriety quickly extended to music academies and conservatories. Suddenly, the playing style was expected to be subservient to the composition. The former classical solo school and its glorification became a thing of the past. Precise tutti playing and the faithful execution of all instructions given by the composer were now more important than melodic playing and free interpretation.

Belcanto is Back

In the 1990s, a miracle happened: music teachers and musicians started demanding to focus on the melody and its presentation. To be fair, it wasn’t really that miraculous: I still remember how Maurice André enthralled his audiences in the 1970s with amazingly long melodic arches in the grand romantic tradition. In my view, it proved that music is first and foremost about passion rather than clever constructions.

The Mission of Musical Interpretation

And yes, a musician’s main task is to structure and guide a melody. The new stars on the music scene show us how captivating a melody presented with passion can be. We can learn by simply listening to them. Belcanto is back! So let’s convey this craft to our students by showing them how to expertly connect one note to the next, how to create tension using emotion, dynamics, accents and tempo variations.

Only then will music come to life.