Tips and prerequisites for brass sections

A section really only sounds like one if all its members consider themselves team players and act accordingly. Producing a homogeneous sound, style and tempo ultimately also means that one has to be critical of oneself. Sounds like philosophy, doesn’t it?

An orchestra is the wrong place for showcasing one’s talent: it is first and foremost a team effort.

Just imagine playing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 (all men will be brothers...) with a bunch of individuals working against one another"”can’t do that, right? Achieving a satisfactory section sound is a matter of will and conviction

Note that a tight section sound is not necessarily the result of clone-like or formatted musicians. My colleagues of the ARTA trumpet ensemble play widely different trumpet models (i.e. Perinet and rotary valves), yet we still sound like a unity.

Only by accepting the diversity of our fellow musicians and their sound characteristics will we be able to create a uniform section or ensemble. Sounds rather philosophical, doesn’t it?

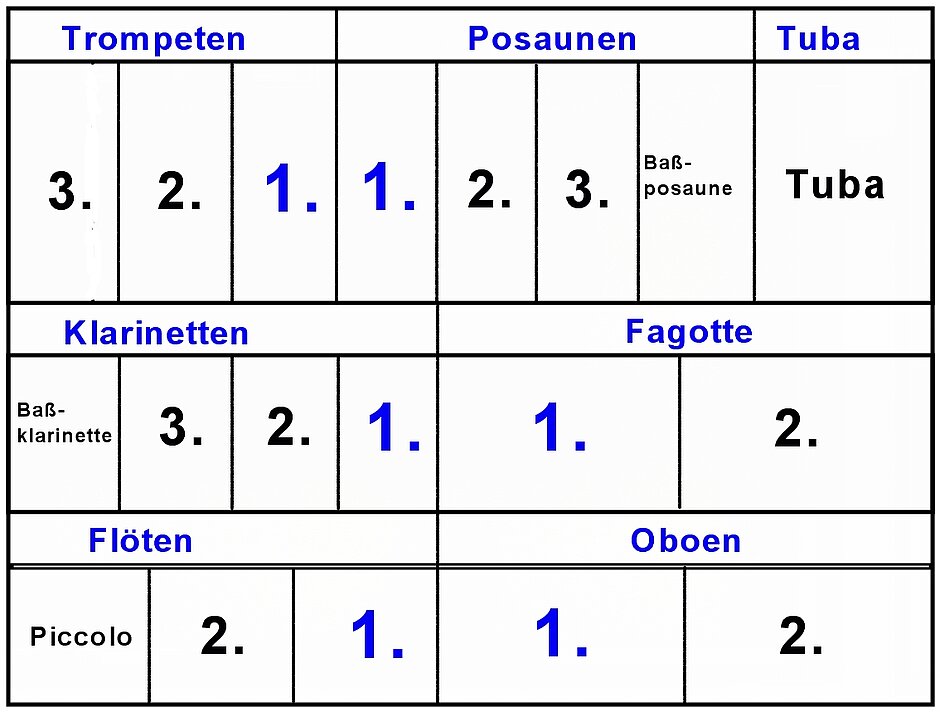

Distribution of the registers

The arrangement/location of an orchestra’s sections can have significant consequences for its overall sound. I agree that there are vastly different ideas about acoustics and sound character. Yet, shifting softer sections to a different location may boost their prominence. Just be creative and pay attention to the location’s acoustics before making up your mind.

Another consideration is how to seat the various parts: should the 1st parts of two different sections be seated next to each other, thus improving visual and musical contact?

Some composers favor parallel voicings across several sections, and brass bands often play music with parallel saxophone, horn and tenor horn registers. Grouping such sections therefore makes sense. As for the horns, you may consider seating them as usual (with the bell towards the hall’s rear) or rather in such a way that their sound is projected at the audience.

Individual prerequisites for musicians

Let us agree that "adaptability" is the magic word here.

Obviously, all musicians need to have the technical ability to play the music in a meaningful way. After all, the overall performance is only as good as the weakest link. Therefore, the musical result is necessarily a compromise of all available skills.

The basic aspects are timing and quality of the notes. Depending on the work at hand, different timbres may be called for, i.e. a rounder sound for belcanto-style melodies, and a low-fat, technically precise sound for virtuoso compositions. Especially wind players can do a lot with their mouth cavity to alter the sound.

A section’s rhythmic presence in syncopated passages needs to make sense. The section leader needs to pay attention to synchronization. An "Egerländer" syncopation style, for instance, won’t work for a symphonic composition. It’s a matter of style.

But it is safe to say that sloppy timing ruins even the most harmonious section sound.

Exercises to instill the "section spirit"

1. "Chord competence":

Playing chords in both root position and various inversions is a staple of section work. Therefore, all musicians need to be aware of how chords work.

2. Learn to listen:

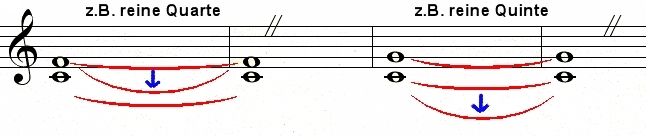

Though not every individual is able to hear perfect pitch, this can be acquired up to a point.

Tip: play an interval and ask the bottom part to raise and lower its pitch. This works best with pure intervals. After a while, untrained colleagues automatically adapt to the bottom part’s pitch, because pitch (or intonation) is crucial for a convincing sound.

3. Important and ancillary notes:

Sometimes, less is more. While practicing chords in root position with your section, ask the fundamental, the third and fifth to take turns in playing just a wee bit louder to find out how that affects the overall chord. Such conscious practice will lead to a more transparent chord sound.

4. Practicing timbre variations:

Timbre variations within a section during sustained chordal passages allow the section members to contribute to the composition’s overall sonic requirements.

Exercise

Change a chord’s romantic timbre to a harsher, smaller one without changes to the playing dynamics. The orchestra or section leader could use special signs to indicate when and how to change.

5. The aspect to pay attention to is that changing this parameter must not affect other criteria.

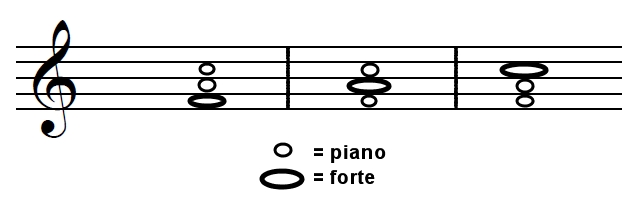

The timbre’s independence from note length:

Start out by playing long chords with the section and specify the timbre to aim for: round, full, etc. Repeat this chord with a short note. The sound must not change, because "piano" doesn’t mean "smooth" (it just means "soft"), while "forte" should not be confused with "aggressive".

The same is true of crescendo/decrescendo.

The most important element of this element is that all individuals contribute to the common benefit.

So it »is« a philosophical endeavor after all...

Have fun and all the best!