Introduction

I do hope you’ve had some time to study the first theoretical workshop published a few weeks ago. This second part is the continuation of that workshop"”and completing it only makes sense if you have understood the first part. I suggest you store both parts in a safe place to have something you can fall back on if you need some music theory.

After discussing major scales, the circle of fifths and scales in general, let’s look at notes you play simultaneously:

Chords

Chords consist of at least 3 notes that are played simultaneously. The first note is called the "fundamental", the second is the "third" and the third note is called the "fifth". Ah, you are already aware of two of these terms, are you not? So let’s add a few more... the third specifies whether a chord is major or minor. A minor third produces a minor chord, a major third a major chord. You already heard of those, too! The fundamental and fifth hardly ever change"”the third does all the work to distinguish between major and minor.

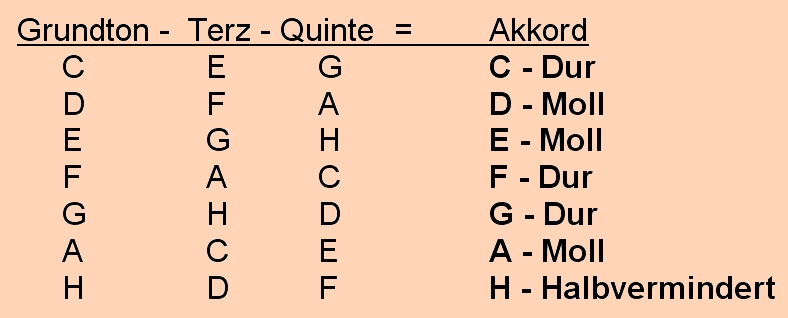

Let’s look at C major for an illustration of this:

...there again is that strange note at the 7th step of the C major scale, which doesn’t contain a pure fifth. The pure fifth of B would be F#. Yet, the F# is not part of the C major scale. See the explanation below. Obviously, this system can be applied to all other keys (see the circle of fifths).

The sequence of major and minor chords is fixed. I hope you noticed that the sequence of major and minor chords corresponds exactly to the sequence of major and minor scales!

Looking at these chords, you will notice that there are 3 major chords. That explains why so many songs can be accompanied using just 3 major chords!

If you do need additional chords, these are often scalar chords, i.e. chords that can be built using a major scale. For reasons of simplicity, the term "step" is used, which somehow makes sense when you talk about scales...

Chords have a fixed function. It may strike you as remarkable that certain chords are often followed by the same chords. Let us return to the "steps". These are indicated by means of Roman numerals. For C major, the system is as follows:

In addition to that, there are a few technical terms of which you should remember at least the bolded entries.

What purpose do chords serve?

You probably know that I’m a jazz musician, and so you may be tempted to believe that what I’m telling you here is only for jazz. Wrong!

The concepts explained here are related to classical, European harmony. It is the foundation for classical, folk, rock, blues and...yes... also jazz. But if you decided to study Johann Sebastian Bach’s compositions, for instance, you would notice that even he already went way beyond the theoretical constraints.

Do you know the feeling when you need to sing or play a songs whose original key to high or too low for your (or somebody else’s) voice? Or of your band’s trumpet player who has a hard time playing those high notes...

Those able to play such a song in a different key (something we call "transposing") clearly are at an advantage. Any singer and any instrument can put everything I tell you here to good use!

Let’s look at a simple blues, for instance. The simplest blues structure is based on 12 bars. Let us stick to C major here:

C/C/C/C/

F/F/C/C/

G/F/C/C (G)

Only three chords (the three scalar chords) have kept generations of blues musicians, boogie-woogie piano players, rock’n’roll, soul, funk and gospel musicians, the Beatles and any other act busy"”a mere three chords.

The seven steps of chord sequences

I would like to explain the reason for the names given to the seven chord steps.

Tonic: This is the basis where everything starts and to which everything returns

Supertonic: It shares two notes with the subdominant

Mediant: Shares two notes with the tonic

Subdominant: The chord below the dominant

Dominant: It always leads you back to the tonic

Submediant: This minor chord shares two other notes with the tonic

Leading note chord: The notes of this chord correspond to the dominant notes with a seventh. This chord, however, doesn’t contain the fundamental and is therefore called a rootless chord.

Although this is not something you need to remember, knowing how chords area related to one another is always a good thing. Let us look at a few sequences:

The II - V - I sequence (in C major, this corresponds toD min, G, C)

It is used on countless songs and pieces.

Listing examples for all recurrent chord sequences is impossible, I’m afraid. Bach, Bon Jovi, Billy Idol; from Abba to Zappa... just listen to them for new chord sequences or the ones explained here.

Let’s look at another important chord sequence, the "turnaround", i.e. the sequence one could play for hours on end.

In C major, the turnaround looks as follows:

A min, D min, G, C

This is the II-V-I sequence with the chord at the sixth step.

Thus: VI-II-V-I

This sequence is used over and over in all music genres. It could be played indefinitely, because the end is also a new beginning. It only contains scalar chords!

Half-diminished chords

BØ, the half-diminished chord. So far, we have successfully managed to avoid this strange fellow. But we simply have to take a closer look at it. As indicated by "diminished", one important constituent note is altered here.

If this chord at the 7th step of the C major scale (B half-diminished) were a normal minor chord, it would contain a pure fifth in addition to the fundamental and the minor third (3 ½ steps). Given that F# is not part of the C major scale, the fifth of this chord is diminished.

This explains why this chord is often indicated by means of the following symbol Bmb5 ("B minor flat five"). Why is this chord "half-diminished"? Because there is another chord called "B0" (B zero) or Bdim (diminished), i.e. the "real" diminished chord (B, D, F, Ab). Although it contains the same notes as its half-diminished cousin, its fourth note is the minor seventh (which, strictly speaking, is a sixth, but sounds so much different in this configuration that using a different name makes sense).

Diminished chords

Diminished chords consist of stacked minor thirds, and so B, D, F, Ab is "B dim". Now lets invert this chord, i.e. with the B in top position and the D as root: D, F, Ab, B... again a stack of minor thirds. But since the D acts as root here, this chord is called "D dim".

This is a game we could play for hours on end: F, Ab, B, D is F0, and Ab, B, D, F is Ab0. Hang on: I learned one chord, and now it turns out I discovered three more. Wait a minute: there are only 12 different notes. So, if I can use one note to build 4 different chords, it would be fair to say that"”strictly speaking"”there are only 3 diminished chords. See, that wasn’t difficult, was it? Note that merely reading my explanation is probably not enough"”you need to analyze it to put it to good use. And remember that a brass instrument may not allow you to play chords, but you can play the notes they contain one after another ;-)!

How do you improvise?

If you think this question is not funny, just think of all the big bands, school brass bands, etc., where somebody occasionally gets to play a solo. And I’ve long stopped counting how many times people ask me to explain in a nutshell how to "improvise?".

Chord symbols on a score indicate the scales you can play in those places and which chord notes you can use. Obviously, playing acceptable notes at the right time may not be enough to impress your audience, but knowing the vocabulary is crucial for the creation of well-formed sentences.

Just think of Stevie Wonder who once sang "Music is a world within itself, with a language we all understand". So, for now, keep studying the words of this fascinating language called music. Have fun!

Yours,